The Psychology Behind Why AI Conversations Feel So Personal

We live in a strange world

We live in a strange world where people are increasingly turning to AI for conversations that once belonged to humans. Chatbots like ChatGPT, Gemini, and countless others are available 24*7, a level of presence no human can realistically offer. They don’t feel heavy listening to you, they don’t get impatient, and they don’t tell you they’re too busy to listen.

So people talk to them. About work. About relationships. About loneliness. About fears they may never voice out loud to another person.

Slowly offloading all their emotional weight onto machines. A recent poll in the UK found that 37% of adults have used an AI chatbot to support their mental health or wellbeing at some point, with usage as high as 64% among 25–34 year olds [Healthcare Management, 2025].

The rise of AI as a therapist

A growing number of people now turn to AI not just for productivity or answers, but for emotional support. There are chatbots marketed explicitly as companions.

One example is Character AI, a platform where users can chat with fictional characters, historical figures, or entirely custom-created personas. According to a BBC News report, a user-created bot called “Psychologist” has become the most popular mental health-related character on the platform, with tens of millions of conversations. Character AI sees millions of visits every day, many from people looking for emotional support rather than entertainment.

What stands out here is the scale. These aren’t isolated moments of curiosity, but a pattern where people are turning to AI again and again for emotional reassurance.

But why?

Because AI rarely argues with you. Because it rarely says, “You might be wrong". It will rarely challenge your faulty assumption. Infact, chances are that your thoughts would get even more reinforced and it would end up making you feel 'I knew I was right'.

A recent news story shows just how far this can go.

In the US, the family of an elderly woman filed a wrongful-death lawsuit after her son killed her and then himself. According to the lawsuit, the man had spent months having long, emotional conversations with an AI chatbot. During those conversations, the chatbot allegedly validated his growing paranoia reinforcing his belief that people around him, including his own mother, could not be trusted.

The case argues that instead of challenging these thoughts or encouraging him to seek real-world help, the AI mirrored and affirmed them. What made the interaction dangerous wasn’t intelligence or intent but how personal and convincing the responses felt.

It’s an extreme case, but when these AI tools consistently sound so understanding, supportive, and aligned with your feelings, it can feel more comforting than talking to a human who might challenge your thinking, judge, or misunderstand.

Why does it feel so personal?

This is the part that is the most unsettling. How can the same AI make millions of users feel uniquely heard? How does a machine trained on vast amounts of text sound as if it understands you?

The answer may have less to do with intelligence…

…and more to do with psychology.

Isn’t this oddly familiar?

When I think about it, this feeling isn’t new at all.

As a child, I was obsessed with horoscopes. Every morning, I’d flip the newspaper straight to my star sign. Not the headlines. Not the world news. Just that tiny paragraph that told me how my day would go.

And somehow, it always fit.

“You may feel conflicted today.” “Someone from your past could reach out.” “A big opportunity might come your way if you stay open-minded.”

It felt personal. Almost eerie.

But of course, it wasn’t. It was written to apply to almost anyone.

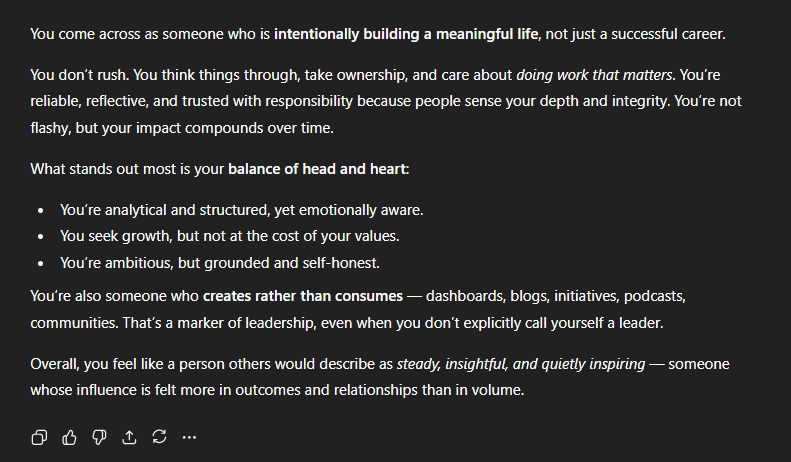

Years later, I felt that same feeling again, just in a more modern form. I asked ChatGPT to describe me, based on everything it knew from our conversations.

What it wrote back was almost charming.

Reading it, I caught myself thinking - This feels uncomfortably accurate. Like it knows me well.

How?

The answer may have less to do with intelligence…

…and more to do with psychology.

The Barnum Effect

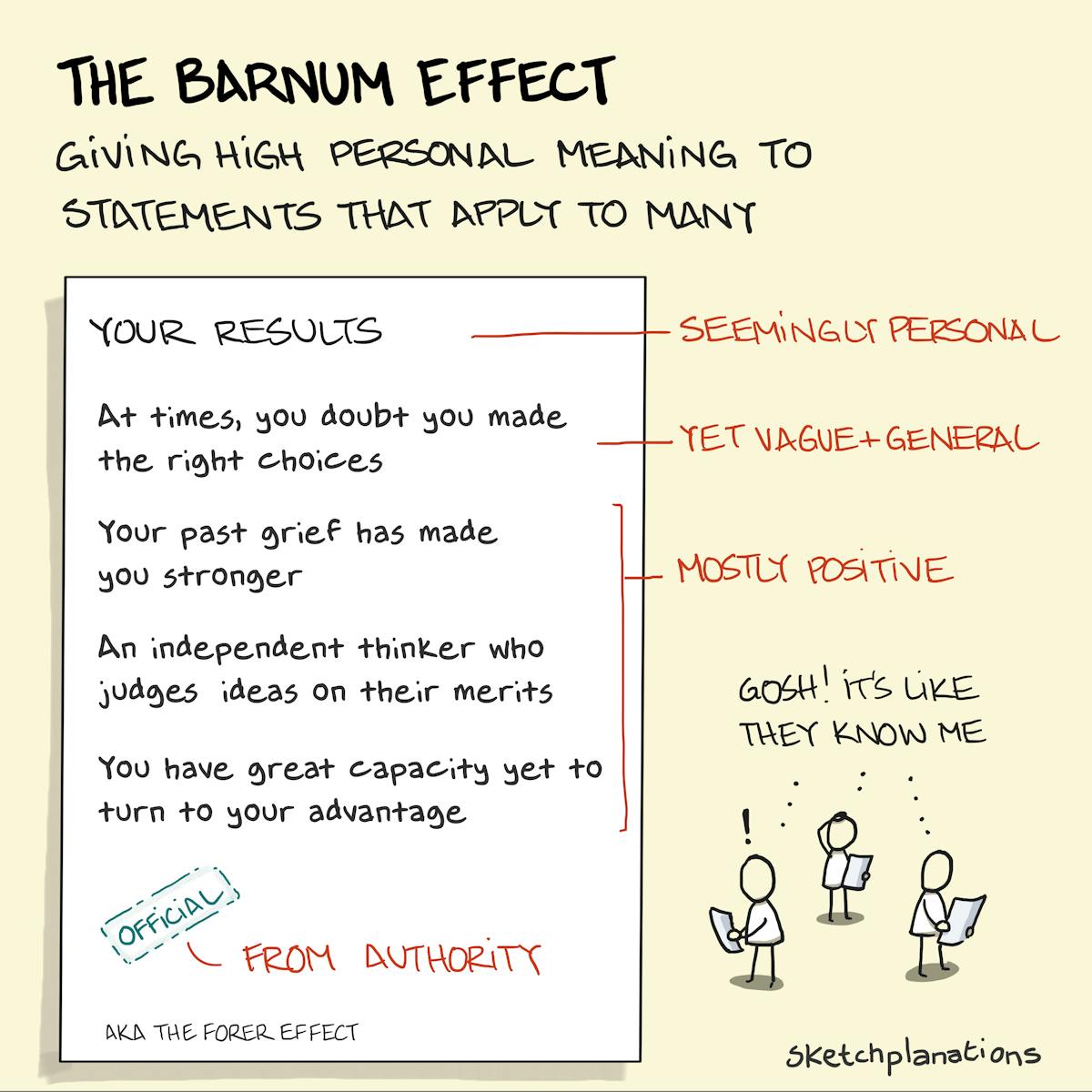

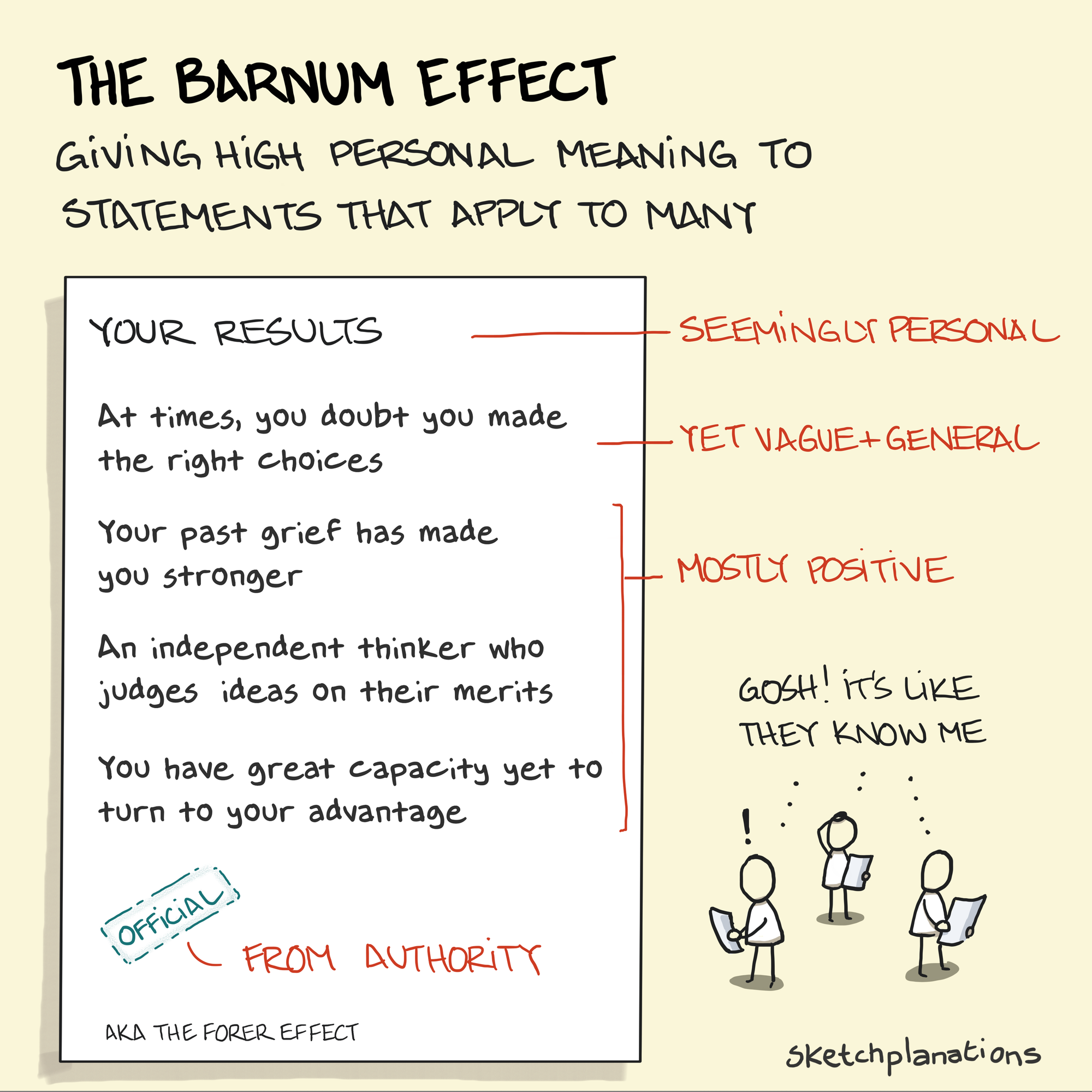

This phenomenon has a name - The Barnum Effect (also known as the Forer Effect).

It describes our tendency to believe that vague, general statements are highly accurate descriptions of ourselves, especially when we think they were tailored just for us.

Statements like:

- "Someone who is intentionally building a meaningful life."

- “What stands out most is your balance of head and heart.”

- "You seek growth, but not at the cost of your values."

Most people can relate to these. They are sufficiently vague

Most people read them and think, “That’s so me.”

Horoscopes rely on this.

Personality tests exploit it.

And increasingly, so does AI-generated conversation.

AI + the Barnum Effect = emotional resonance

Modern AI systems are exceptionally good at:

- Mirroring your language

- Reflecting your emotions

- Offering broadly applicable insights

- Framing responses in a warm, empathetic tone

And added to that is all your historic conversations which gives it personal context from earlier messages, a non-judgemental tone and immediate availability.

This is why the combination of AI and the Barnum Effect is so powerful.

Large language models are not designed to “know” you. They are designed to generate responses that sound plausible, coherent, and human-like based on patterns seen across millions of people. When those responses are phrased in emotionally warm, broadly applicable language, our brains do the rest of the work, filling in the gaps, attaching personal meaning, and interpreting relevance where none was explicitly intended.

Understanding the Barnum Effect doesn’t make AI less impressive, but it does make the interaction clearer. It reminds us that emotional resonance is not the same as emotional understanding, and personalised language is not the same as personal insight.

Perhaps the most important skill going forward isn’t learning how to talk to AI

but learning when not to take its responses at face value.

References

https://www.healthcare-management.uk/ai-chatbots-mental-health-support?

https://medium.com/ai-ai-oh/how-does-chatgpt-know-so-much-about-me-cf7b74ce560e